ARUP Supports Clinicians With Broad Menu, Expert Guidance in Pediatric Laboratory Medicine

Few things elicit a more immediate response than seeing a child suffering, hearing a whimper of pain or fear.

We immediately want to know what’s wrong, and often, the child is not yet capable of communicating why or how they’re hurting.

Clinicians rely on laboratory tests to provide answers, but testing can be complicated when the patient is a child. “Children are not just small adults. They have unique clinical needs,” said ARUP Laboratories Chief Medical Officer Jonathan Genzen, MD, PhD, MBA, who is also ARUP’s senior director of governmental affairs. “Clinicians know that it’s vital that the lab tests they order are appropriate for children, and [that they] are provided with appropriate ways to interpret results.”

More than 10% of tests performed at ARUP are for patients younger than 18 years, and half of ARUP’s hundreds of hospital and health system clients nationwide are medical centers with specialty pediatric care needs or children’s hospitals. In ARUP, they find a reference lab with a broad test menu and a comprehensive, caring approach to pediatric testing.

ARUP has led the clinical laboratory industry in validating pediatric-specific reference intervals for test results interpretation and in advancing innovation in biochemical genetic testing, cytogenetics, autoimmune disease testing, rapid whole genome sequencing, newborn drug testing, and pediatric cancer testing, to name just a few areas of specialization.

ARUP also supports clinicians and laboratory leaders with expert consultations and education that differentiate it from other providers of pediatric testing. “We do have expertise that is recognized beyond ARUP, definitely,” said Joely Straseski, PhD, MS, MLS(ASCP), DABCC, FADLM, head of clinical operations for Clinical Chemistry, Toxicology, and Biochemical Genetics.

A Focus on Pediatric Reference Intervals

Straseski, who is also a medical director of Endocrinology and codirector of the Automated Core Laboratory at ARUP, has been a leader of ARUP’s renowned Children’s Health Improvement through Laboratory Diagnostics (CHILDx™) program, which over time has established reliable pediatric reference intervals for numerous assays important in pediatric care.

Reference intervals specific to children at different ages are necessary to accurately interpret test results because children’s biochemistry changes rapidly as they grow and develop, she said. Appropriate reference intervals therefore must account for continuous physiologic changes.

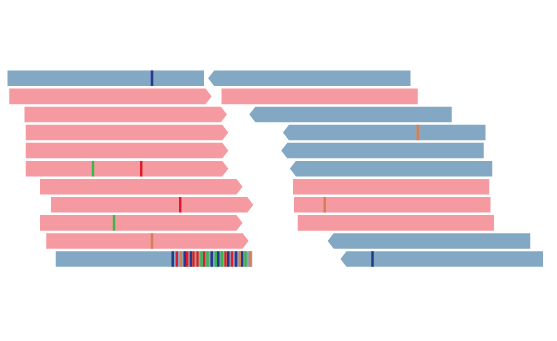

Validating intervals that reflect the gradual nature of development is challenging because it’s difficult to collect enough samples from healthy children across the development spectrum to properly validate reference intervals for different age ranges. CHILDx succeeded because thousands of specimens were collected either during screening before elective surgeries or via community recruitment from healthy children 6 months to 17 years old, with a goal to have from 120 to 240 samples for each year of life from both boys and girls. ARUP built a well-characterized repository of specimens from healthy pediatric patients that enabled a concerted effort to establish intervals for many commonly used tests, resulting in dozens of scholarly publications. Pediatric reference intervals are included on relevant tests in ARUP’s Laboratory Test Directory.

Due to the volume of testing it performs as one of the nation’s four largest reference labs, ARUP also is able in some instances to establish pediatric reference intervals using statistical modeling. Kelly Doyle, PhD, DABCC, FADLM, medical director of Special Chemistry, Endocrinology, and Mass Spectrometry at ARUP, recently did so for a test for glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency, a condition that inhibits the body from protecting red blood cells against oxidative stress.

G6PD deficiency is one of the most common genetic deficiencies and can lead to hemolytic anemia, Doyle said. In newborns, it can lead to even more severe consequences, such as bilirubin neurotoxicity, which occurs when bilirubin—a byproduct of damaged red blood cells—builds up in the brain.

Because ARUP has performed tens of thousands of tests in pediatric patients, it’s possible to use modeling techniques to look at the distribution of test results in the different age brackets and determine reference intervals for different age ranges that indicate G6PD deficiency.

“These reference intervals are only possible when you have sufficient data,” he said. “You couldn’t launch a new test and use this type of approach. You have to have a repository of data already to evaluate.”

Advocating for Test Harmonization

As ARUP continues to add to the base of knowledge about pediatric reference intervals, the company also is engaged in advocacy for national policy initiatives that aim to create a comprehensive, ethnically and geographically diverse repository of pediatric reference interval data, Genzen said.

ARUP was among 42 clinical laboratories, pediatric hospitals, and medical societies and associations that signed a February 10, 2025, letter coordinated by the Association for Diagnostics & Laboratory Medicine (ADLM), appealing to the U.S. House and Senate Appropriations Subcommittee on Labor, Health and Human Services, Education, and Related Agencies, to provide the CDC with $10 million in funding to advance a pediatric reference interval repository initiative.

Without a nationwide effort, gaps will continue to exist for many tests, particularly for certain populations for which data are especially hard to collect, such as premature infants, said Dennis Dietzen, PhD, division chief of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine at Phoenix Children’s Hospital and chairman of the ADLM Policy and External Affairs Core Committee.

He also cited a challenge with “harmonization” of reference intervals for kids. Discord in reference intervals comes not only from the use of biased analytic systems but from differing interpretations of the data that characterize the biochemistry of childhood development. “This lack of standardization limits the generalizability and utility of the intervals,” Dietzen said. “Efforts to harmonize assays across institutions have been ongoing, but significant inconsistencies remain, making it difficult to establish universally accepted pediatric reference intervals.”

He said advocacy efforts have succeeded in raising awareness and garnering moral support from organizations and Congress. “It’s really hard for a congressman to say, ‘I don’t care about children’s health.’ That would be at their own electoral peril,” Dietzen said.

Nonetheless, financial investment is still lacking, he said.

Laboratory-Developed Tests Essential in Pediatric Care

Dietzen and Genzen also noted another challenge for pediatric testing. Many tests common in pediatric care are laboratory-developed tests (LDTs), primarily because commercial, FDA-cleared or approved tests often do not exist for the unique clinical needs of children.

Reliance in pediatrics on LDTs meets an important need, but it also contributes to the harmonization issue because tests, and pediatric reference intervals validated for those tests, vary across institutions and geographic regions, Dietzen said.

Genzen added that regulatory uncertainty around LDTs remains a concern. While a federal court ruling in March 2025 ended the most recent attempt by the FDA to regulate LDTs as medical devices, which potentially would have forced labs to discontinue some tests, congressional action that could result in further regulation of LDTs is still anticipated at some point.

Clinical laboratories are already highly regulated under the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA). Genzen has been a leader in advocating on behalf of clinical laboratories for common sense updates to the existing regulatory framework that are reasonable and predictable so that ARUP and other labs can continue to meet the needs of pediatric patients.

Diagnoses That Save Lives

ARUP is proud of the important role it plays in the practice of pediatric medicine and celebrates when a test leads to lifesaving treatment, as it did in the case of Woody Tribe, who was the first Utah infant to be diagnosed with guanidinoacetate methyltransferase (GAMT) deficiency. Detection of the rare inherited condition resulted from the disorder being added to a state’s newborn screening panel through the efforts of Marzia Pasquali, PhD, FACMG, ARUP medical director of Biochemical Genetics, and Nicola Longo, MD, PhD, a pediatrician who was then chief of the Medical Genetics division at University of Utah Health.

The stories of Beckett Lippincott, who was diagnosed with juvenile dermatomyositis, and Cal Taylor, who was diagnosed with nemaline rod myopathy, are other important examples.

Genzen said ARUP’s test development pipeline is robust and will continue to evolve to meet emerging needs. “If you think about just the spectrum of our extensive test menu and the testing options available, a lot of it really is designed to help serve pediatric patients.”

“Children’s health is a topic that everything can filter through: harmonization, LDTs, and access to testing are key examples,” he said. “Issues that are important throughout laboratory medicine apply especially in children’s health.”

What Is CHILDx™?

The Children’s Health Improvement through Laboratory Diagnostics (CHILDx™) program launched in 1999 as the largest pediatric reference interval study of its kind. Marzia Pasquali, PhD, FACMG, ARUP medical director of Biochemical Genetics, chaired the first board of directors, which was established with representation from 15 institutions.

Why was it created?

The goal of CHILDx has been to establish pediatric reference intervals for a variety of analytes to address a critical need. Before the program began, intervals were often based on small sample sizes, leading to unreliable or nonrepresentative test results.

What did it do?

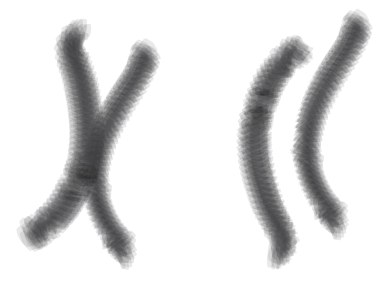

Starting in 2002, blood specimens were collected from thousands of healthy children from 6 months to 17 years old with an eye toward characterizing specimens that were meticulously categorized by factors such as age and Tanner stages (five stages that describe the physical changes of puberty in boys and girls).

This large repository of specimens set the program apart by providing unparalleled access to well-characterized samples that enabled more precise and meaningful laboratory diagnostics for children.

The researchers have created pediatric reference intervals for dozens of analytes and produced dozens of academic papers and abstracts. In addition to Pasquali, they included current and former ARUP experts Ed Ashwood, MD, Mark Astill, MS, Cheryl Coffin, MD, Harry Hill, MD, Nicola Longo, MD, PhD, Wayne Meikle, MD, Sherrie Perkins, MD, PhD, Theodore Pysher, MD, William Roberts, MD, PhD, Joely Straseski, PhD, and many others.

What is CHILDx’s legacy?

CHILDx has made a lasting impact by setting new standards for pediatric laboratory diagnostics and demonstrating the importance of large, well-curated specimen repositories. Its legacy continues to serve ARUP’s clients and to influence the field, especially as new approaches to reference intervals and renewed advocacy efforts seek to build on its foundation.